In this post and accompanying video, I’ll talk about juvenile delinquency and how there are different types of juvenile offenders. I cover the developmental taxonomy by psychologist Terrie Moffitt, who proposed that there are two types of juvenile delinquents: life course persistent offenders and adolescence limited offenders. In developmental psychology and criminology, this idea has been very influential, and I’ll go through the fundamentals.

Table of Contents

The Age-Crime Curve and Juvenile Delinquency

In general, most offenders commit their crimes when they are adolescents or young adults. As offenders get older, they often settle down and commit less crime. But, this is not the case for all offenders; some offenders start to commit less crime when they get older, but others do not. In this post, I’ll explain the idea proposed by psychologist Terrie Moffitt, about how there are two different types of juvenile offenders.

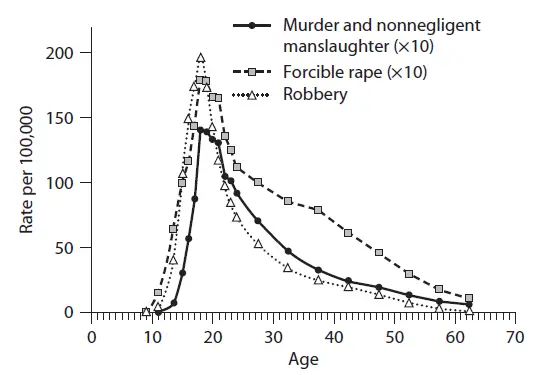

The graph below shows what the development of violence over the life-course usually looks like:

Source: Eisner, M. P., & Malti, T. (2015). Aggressive and violent behavior. ME Lamb (vol. ed.) & RM Lerner (Series ed.), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science, 3, 795-884.

This is a graph for the United States, but it’s widely applicable. What you can see here is a graph of three crime types: murder and nonnegligent manslaughter which is the darker line; forcible rape, which is the dashed line with the squares; and robbery, which is the dashed line with the triangles. On the y-axis, that’s the vertical axis, you can see the number of crimes. And then on the x-axis, that’s the horizontal axis, you can see age, going from about ten to over sixty years old. As you can see, for all three crime types, crime increases dramatically in the teenage years, then it peaks somewhere around age 17 or 18 and then there is another dramatic change when it decreases sharply. So as you can see, the bulk of crime occurs in late adolescence and early adulthood.

Now, this is what is the case for the average person. But, not everybody is average of course. There are differences between people, with some people showing this exact pattern that you see here, and other people not showing this pattern. And it would be really interesting, of course, to see which different patterns exist.

Life-Course Persistent Offenders

And exactly those different patterns were teased out in one of the really influential pieces of research that has been done in this area, which was done by psychologist Terrie Moffitt. In that study, she looked at the different pathways, or criminal careers as they are also called, of youth offenders, and at when they got into crime and when they stopped. According to Moffitt, there are basically two groups of teenage offenders, or two types of what is called “trajectories”. The first group is that of the so-called life-course persistent offender. This trajectory starts early in life. These children start to show problem behavior early on. As you can see in this graph, Moffitt proposed that this is only a small group of adolescents who show this type of behavior, less than ten percent. But their criminal career is very lengthy and consistent, and continues well into adulthood.

Adolescence-Limited Offenders

The second group of offenders, Moffit calls “adolescence limited” offenders. These youths offend only in their teenage years. So their involvement in crime is only temporary. And once they get older, they stop offending. This is a much larger group of youth. So many more youth belong to this group of the adolescence limited offenders than to the other groups, but they commit offenses for a much shorter time period.

The Causes of Juvenile Delinquency

What’s interesting is that according to Moffitt, the causes for juvenile delinquency are different for these two groups, so for the life-course persistent versus the adolescence limited offenders. The life-course persistent offenders may have, for example, genetic or neurological deficits, or they may come from a difficult home environment. They come from problematic backgrounds and have certain characteristics that make their risk of offending very high.

On the other hand, according to Moffitt, the adolescence-limited offenders do not really come from a problematic background. Instead, so many youths commit delinquency in their teenage years, that she considers it almost normative. The causes of juvenile delinquency for this group are very different. These kids are suffering from what is called the maturity gap. Meaning that these youth are biologically mature, their bodies are almost like an adult body, but they’re not allowed to do what adults do. They’re not allowed to work, to drive a car, to marry, or to buy alcohol. They’re basically dependent on their parents and their family and they can’t make many decisions for themselves. But they want to make their own decisions. And so they may start to steal the things they’re not allowed to have and take risks and do things that their parents would never allow them to do, and so they’re looking for new challenges to prove that they are more than capable of conquering them. In this sense, every time a youth does something that adults may think of as bad, for them it is a statement of personal independence.

So even though crime peaks in the teenage years for the average person, Moffitt’s model shows that there are differences between people. Whereas for most youths, crime is something that occurs only in the teenage years and not thereafter, this is the adolescence-limited group of offenders, there is a small group of people who start to show problem behavior already in childhood and for whom it continues well into adulthood. And this group is called the life-course persistent offenders.

You can find the study by Terrie Moffitt here: https://ibs.colorado.edu/jessor/psych7536-805/readings/moffitt-1993_674-701.pdf

This video is part of my FREE criminal psychology course “Explaining the Criminal Mind in 60 Minutes.” You can get access for free here