The book “The Jack-Roller” is an absolute classic in criminology. The book was first published in 1930 and tells the life story of Stanley, who was a young delinquent in Chicago. Clifford Shaw, who is the criminologist who wrote the book, first contacted Stanley when he was 16 years old, and then followed him over the next 6 years to help write Stanley’s life history. This post covering a “The Jack-Roller Summary” provides a concise overview of the main points from the book.

Table of Contents

The Jack-Roller as a Life History

Why is this book so famous? Because it’s one of the first life histories that was published in sociology and criminology. It was actually part of a series of 200 similar studies on juvenile offenders and was published as an example of what a life history can look like. It’s a great example, too, because Stanley wrote part of the book himself and his writing is of exceptional quality.

So in this study, Stanley was interviewed a number of times and also gave a 250-page typewritten description of his life and what his reaction to the events that happened in his life had been. The research team also obtained official arrest records, medical reports, and other documents to make sure that what Stanley told them was authentic and reliable.

The Jack Roller Summary: His Criminal Career

So let’s first have a look at Stanley’s delinquent career, which began at a very early age. He was only 6,5 years old when he started committing crime, which was even before he started going to school. Over the next years, he was found by the police and/or arrested many times for stealing, truancy, and running away. Of course, those arrests are only the tip of the iceberg, because most of the times, he wasn’t caught by the police. When Stanley got older, he proceeded to other types of crime, including burglary and jack-rolling. Jack-rolling means committing robberies on drunk men and homosexual men who approached him.

Stanley was sent to institutions many times, first to the Juvenile Detention Home and later to reform school. By age 10, Stanley describes himself as being an “old-timer” at the Juvenile Detention Home, because by that time, he’d already been there 13 times and was described by the police as a “professional runaway”. At age 16, he spent a year in the Chicago House of Correction.

Risk Factors for Stanley’s Criminal Career

Now, one obvious question that one can ask is what factors might be responsible for Stanley’s quite extensive criminal career. Just to note, these are not meant as excuses, but as explanations to try to understand the factors that can motivate a person to commit crime.

Stanley’s first words in the book say a lot about how he thought his delinquent career started:

“To start out in life, everyone has his chances—some good and some very bad. Some are born with fortunes, beautiful homes, good and educated parents; while others are born in ignorance, poverty, and crime. In other words, Fate begins to guide our lives even before we are born and continues to do throughout life. My start was handicapped by a no-good, ignorant, and selfish stepmother, who thought only of herself and her own children.” (p. 47).

In other words, Stanley blames external factors and not so much his own choices for his criminal behavior, but looking at the situation that he grew up in, he certainly has his reasons. Here is a brief run-down of Stanley background, as discussed in the book, where it becomes clear that Stanley’s criminal career consists of a series of responses to the situations that he found himself in.

- Discrimination of his stepmother against him in favor of her children. First, Stanley came from a difficult home background. Stanley’s mother died when Stanley was four, and shortly after that, his father remarried. Stanley’s dad was an excessive drinker and beat his wife, who in turn beat Stanley and his siblings. Stanley said that he developed a lot of fear and hatred towards his stepmother because she discriminated against him and his siblings in favor of her own children.

- Neighborhood tradition of stealing. His stepmother also made Stanley go out and steal, but it wasn’t just she who encouraged Stanley to do that, it was a neighborhood tradition. Stanley grew up in some of the grimiest and least attractive neighborhoods of Chicago where stealing was a common practice among the children and approved by the parents.

- The adventure and freedom offered by exploring a disorganized area. Stanley started spending more and more time on the streets, and he describes this as an exciting and adventurous time. In his words, “in the neighborhood, life was full of pleasure and excitement.” At 6,5 years old, Stanley ran away from home and started living on the streets. He explained, “Once away from home, the other times were easy. That was the easiest way to get out of my stepmother’s reach, and, besides, it made a strong appeal to my young and adventurous spirit.” In other words, he experienced a sense of adventure and freedom that was offered by exploring the disorganized area where he lived.

- The thrill of adventures in crime. Stanley had certain personality characteristics that made his involvement in crime more likely, such as his tendency to impulsivity and thrill-seeking. About stealing, he said, for example, “How I loved to do these things! They thrilled me. I learned to smile and to laugh again. It was an honor, I thought, to do such things with William.” William was his older stepbrother with whom Stanley went out into the streets. Which brings us to the influence of the boys he hung out with.

- Code of an opressed group and education in crime. At a very young age, 6 or so, Stanley became a member of a street gang with mostly older boys who engaged in stealing and burglary. Later on, when he spent time in correctional institutions, Stanley met other delinquent boys and men he learned from and spent time with. He learned the code of this group, like how to live, how not to tell on others, and what to aim for in life. In other words, Stanley internalized the code of this oppressed group and received an education in crime.

- The repression of treatment in the correctional and reformatory institution. At age 9, Stanley was sent to reform school where the rules and punishments in his perception were so severe and unfair that he developed a strong hatred towards authority figures. He said, “Under the strict discipline restrictions and fears, I rebelled and harbored vengeance and hate. The officials thought they could cowhide and beat reform into me. But my thoughts were far away from thoughts of virtue and being good. (…) Everybody told me to be good and reform, but how could I do better in such a world in such a hole of discipline and coldness? I wanted to get ahead in a criminal line, instead of being good.” (p. 73) So the repression of treatment in this correctional and reformatory institution only motivated Stanley more to continue his criminal career.

- The easy money quickly obtained and spent. In his teenage years, Stanley lived a restless life, finding and quitting jobs, and living on the streets. A few times, he had some money that he’d made and spent it, which taught him that, in his own words, “This little spurt of fortune and adventure had turned my head. Now I wanted a good time.” (p. 85) This is when he started jack-rolling. He wanted a life of adventure and jack-rolling allowed him to make easy money quickly and then spend it.

- The dullness and monotony of the chances to reform offered to him. It was not like Stanley did not get chances to turn his life around. At one point, he was taken in by a wealthy couple, lived with them, and had a reasonably good job. But he said that he missed the streets and felt like he fell out of place. In his words, “My adventurous spirit rebelled against this dry life and it soon won out. (…) What’s the use of having riches if you can’t enjoy life?” (p. 88) So he returned to the streets and started jack-rolling and committing burglaries again with a group of friends instead of accepting the dullness and monotony that came with the chances to reform that were offered to him.

The Jack Roller Summary: Turning Point

All in all, at age 17, Stanley was a hardened offender. He had just gotten released after a year in the Chicago House of Correction and, at that point said that, “I had spent my life going in and out of jails, and now I was old and hardened at seventeen, had lost all hope of regeneration. In fact, I could see nothing but crime and jails bars ahead. That was all I was educated for; it was all my mind could think about; it held lures and hopes which nothing else did. Besides, all my friends were criminal, and I could not escape them.”

It looked as though Stanley’ future was set in stone, but then a turning point came. Stanley called the researcher who had been following him for so long, namely Clifford Shaw, and Shaw tried to set things up for Stanley. Stanley was placed in the home of a respectable family in a good neighborhood, which affected him in the sense that he wanted to improve his own life up to their standards. He got a job that was not so monotonous and that he enjoyed and started going to evening-school classes. He also stopped hanging out with the people in his old neighborhood and started to think of himself as somebody with dignity, feeling proud of himself. He said, “I was on the right road, and I knew it, and I inwardly was elated with myself. The world was losing its cruelness and seemed to have more kindness and love.”

During this time, he also fell in love, and later on married and had a child. By the time the book ends, Stanley, despite his extensive criminal past, is living a regular life and no longer commits crime. In other words, the changes in his life after he was released from the Chicago House of Correction helped Stanley to change his ways, despite his difficult background. He moved to a good neighborhood, stopped hanging out with his old friends, got a job, and married.

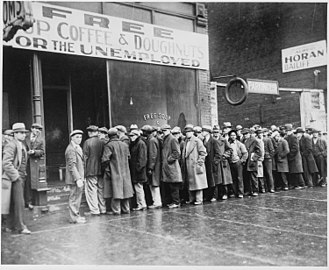

The Jack Roller Summary: Aftermath and Return to Offending

This is the point where the book ends. The book was such a classic that fifty years after the initial study, another criminologist, namely Snodgrass, went looking for Stanley to see how the rest of his life had been. It turned out that, although Stanley had managed to stay out of crime for five years and never returned to jack-rolling, had lost his job in the Depression, committed an attempted robbery, had significant marital issues, and ended up in a mental hospital. Later on in life, he remarried and retired on Disability and Social Security. At the end of his life, Stanley said, “In ending, I would like to dwell on how fortunate I am to have lived through the early traumatic years and yet to have emerged relatively unscathed. There must be protective angels for a boy such as myself that lacked the usual blessings of a home and family. I shall always remember, however, the humble days of adversity, living in the shadow of the horn of plenty.” Stanley died in 1982 at age 75.

The Book as a Product of the Chicago School

OK, so this is in a nutshell “The Jack Roller Summary”. The author of the Jack-Roller, Clifford Shaw, was part of the Chicago School, a group of sociologists in the 1920s and later who studied the ecology of city life in Chicago, including, for example, how juvenile delinquency was embedded in Chicago’s neighborhoods, and how Chicago as a city affected people’s criminal behavior. As part of their research program, these sociologists were also very much interested in documenting life histories.

As such, “The Jack-Roller” must be seen in connection with the rest of the work of the Chicago School. It was a small part of a bigger whole, namely of the larger ecological sociology that the Chicago School was developing.

Original source for “The Jack Roller Summary”:

Follow-up source for “The Jack Roller Summary”: